Chip makers brace for slower pace in Moore's Law By Lucas van Grinsven and Nathan Layne TOKYO (Reuters) - The journey to ever smaller, faster and cheaper chips is slowing down and may put a big dent in sales and profits of the semiconductor sector and even the economy, industry players and analysts said this week. Until recently, chip makers doubled the capacity of their products at the same size and cost every 18 to 24 months, helped by miniaturization and scale advantages, a phenomenon known as Moore's Law, named after the Intel co-founder Gordon Moore who predicted this trend as early as in 1965. As Moore predicted, a transistor that cost about $1 in 1968 dropped to just under 10 cents in about five years. The cost again fell 10-fold every four to five years until 1985 when the cycle lengthened to seven years, according to Intel and Dataquest data. Technically, his trendline continues, with lithography machines steadily shrinking the detail on a chip from 130 nanometers in 2001 to 90 nm in 2003 to 65 nm 2005 and set to move to commercial chips with 45-nm detail in 2007. Miniaturization boosts chip processing speed by cutting down on the distance the electric load must travel. But only the biggest chip producers are installing the latest and most expensive machines. This is effectively slowing down Moore's Law, chip makers say. (read full article)

Friday, September 16, 2005

Moore's miniaturization dream

Friday, August 12, 2005

Monday, August 08, 2005

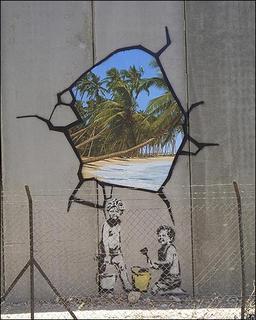

BBC NEWS : Art prankster sprays Israeli wall

In a peace and conflict issues class I took last spring, I had the opportunity to see some images of the West Bank barrier being built during an excellent talk by a young Isreali refusenik about his first-hand experiences in Israel. The images he showed included his own photographs -- striking in content and composition -- of the wall that definitely remained embossed in all our minds even several months later. Many of us particularly recalled a particular photograph of the barrier wall along a highway with contrasting colorful "Brave New World" like murals painted on depicting a world that doesn't exist in those parts.

Today, a friend of mine sent me an article about a similar story reported on BBC NEWS Online. This one a tearful satire.

In a peace and conflict issues class I took last spring, I had the opportunity to see some images of the West Bank barrier being built during an excellent talk by a young Isreali refusenik about his first-hand experiences in Israel. The images he showed included his own photographs -- striking in content and composition -- of the wall that definitely remained embossed in all our minds even several months later. Many of us particularly recalled a particular photograph of the barrier wall along a highway with contrasting colorful "Brave New World" like murals painted on depicting a world that doesn't exist in those parts.

Today, a friend of mine sent me an article about a similar story reported on BBC NEWS Online. This one a tearful satire.

Secretive "guerrilla" artist Banksy has decorated Israel's controversial West Bank barrier with satirical images of life on the other side. (Full Story)

Sunday, August 07, 2005

Thursday, July 28, 2005

nanonanomonstertrucks

Richard Feynman believed that devices and materials could someday be fabricated to atomic specifications when he said, "The principles of physics, as far as I can see, do not speak against the possibility of maneuvering things atom by atom."

This scientific ideology came to be widely known as nanotechnology.

Then "nano" became buzzword for the PR and advertising agencies.

Now, nano-hummer.

A sense of sarcasm engulfs my mind when I see this billboard across from our local nano-supermarket; the word "nano" applied to such a quintessential example of the American obsession with gargantuan existence.

Richard Feynman believed that devices and materials could someday be fabricated to atomic specifications when he said, "The principles of physics, as far as I can see, do not speak against the possibility of maneuvering things atom by atom."

This scientific ideology came to be widely known as nanotechnology.

Then "nano" became buzzword for the PR and advertising agencies.

Now, nano-hummer.

A sense of sarcasm engulfs my mind when I see this billboard across from our local nano-supermarket; the word "nano" applied to such a quintessential example of the American obsession with gargantuan existence.

Business Week publishes 2005 "Top 20 Innovative Companies in the World"

Here is a poll for those who may find such news interesting. I always do, particularly when I am looking for companies to work for. Not surprised, but pleased, that Apple leads the group with significant margins. Click to view the original article on Business Week Online.

Source:

www.businessweek.com/magazine/content/05_31/b3945407.htm

Here is a poll for those who may find such news interesting. I always do, particularly when I am looking for companies to work for. Not surprised, but pleased, that Apple leads the group with significant margins. Click to view the original article on Business Week Online.

Source:

www.businessweek.com/magazine/content/05_31/b3945407.htm

Friday, July 15, 2005

Saturday, July 02, 2005

nomadicLens Wallpaper: "La Corrida de Toros"

Monday, June 27, 2005

Words of Wisdom : "Stay Hungry, Stay Foolish"

This is one of the best things I have read in recent weeks. Extremely motivating. I have been feeling lost in my meaningless days at my corporate job that I know I should leave. Just don't know how. This speech reignited my spirit to follow through with what I truly love and not to settle. I just read it a couple of days back -- and it inspired me to begin re-focussing on my photography again and do something with it. Who knows if I will be anywhere as successful as Steve Jobs has been following his dreams, but at least it has given me a momentum.

Here's an excerpt:

This is one of the best things I have read in recent weeks. Extremely motivating. I have been feeling lost in my meaningless days at my corporate job that I know I should leave. Just don't know how. This speech reignited my spirit to follow through with what I truly love and not to settle. I just read it a couple of days back -- and it inspired me to begin re-focussing on my photography again and do something with it. Who knows if I will be anywhere as successful as Steve Jobs has been following his dreams, but at least it has given me a momentum.

Here's an excerpt:

Your time is limited, so don't waste it living someone else's life. Don't be trapped by dogma - which is living with the results of other people's thinking. Don't let the noise of other's opinions drown out your own inner voice. And most important, have the courage to follow your heart and intuition.Full text of Steve Jobs' Commencement Address delivered on June 12, 2005 at Stanford. Commencement Address on video.

Tuesday, May 17, 2005

Galloway: Knockout on Capitol Hill

If you get a chance to see the news tonight, look out for this news story. It might be worth watching. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk_politics/4553601.stm George Galloway is an ex-member of Tony Blair’s Labour party who was recently kicked out of the party for constantly criticising Blair and Britain’s involvement in the Iraq war. He was also accused by some U.S. senators of receiving bribes from Saddam Hussein as part of the now discredited U.N. oil for food program. Today he's in front of some committee on Capitol Hill investigating that program. From what I’ve read here he seems to be giving as good as he gets and introducing a bit of robust, argumentative British parliamentary style debate into Capitol Hill. I look forward to seeing these exchanges on T.V. tonight.Here is a link to another related article ("Galloway takes on US oil accusers") on the BBC website. Check out the video on the website of Galloway's Senate testimony, if you missed the news clips tonight.

Thursday, May 05, 2005

mindFrame PhotoCanvas Series: NW Magazine Covers (march 1938)

The dates have significance, some related to the photographic content, some related to the place where the original photo was taken, and others just chronicle of events that that have taken place in the history of our planet.

NW signifies...

Well, it is open to viewer's imagination. Feel free to comment.

Tuesday, April 19, 2005

Coldplay's New Album Cover for 2005 release

Check out this blog entry on stereogum.com site about a secret code on Coldplay's New Album Cover and various stabs at cracking the code in the comments section.

Check out this blog entry on stereogum.com site about a secret code on Coldplay's New Album Cover and various stabs at cracking the code in the comments section.

Sunday, April 17, 2005

mindFrame PhotoCanvas Series: "Street, Woman, Notebook - A Photographer's Muse"

mindFrame PhotoCanvas Series:

"Street, Woman, Notebook - A Photographer's Muse"

Photographed in Bolivia (2003)

Here is an interesting article published in Seattle Times (April 09 2005), IMF policies seen firsthand in Bolivia, interviewing two University of Washington students Carolyn Claridge and Nicholas Verbon about their research on a report on how the International Monetary Fund has caused trouble with the Bolivian economy.

The full report authored by Jim Shultz, Deadly Consequences: The International Monetary Fund and Bolivia's Black February (downloadable PDF version) is available on The Democracy Center website.

mindFrame PhotoCanvas Series:

"Street, Woman, Notebook - A Photographer's Muse"

Photographed in Bolivia (2003)

Here is an interesting article published in Seattle Times (April 09 2005), IMF policies seen firsthand in Bolivia, interviewing two University of Washington students Carolyn Claridge and Nicholas Verbon about their research on a report on how the International Monetary Fund has caused trouble with the Bolivian economy.

The full report authored by Jim Shultz, Deadly Consequences: The International Monetary Fund and Bolivia's Black February (downloadable PDF version) is available on The Democracy Center website.

Friday, March 04, 2005

Nanotechnology "chatter"

ENOUGH NANOTALK: MATERIALS AND KNOWING HOW AND WHEN TO USE THEM SPEAK VOLUMESBy Daniel Colbert Small Times Guest Columnist Feb. 28, 2005 – In his novel "Cat's Cradle," Kurt Vonnegut created three new words suitable for nanotechnology. Vonnegut defines the words in his collection of essays, "Wampeters, Foma, and Granfalloons": "A wampeter is an object around which the lives of many otherwise unrelated people may revolve. The Holy Grail would be a case in point. Foma are harmless untruths, intended to comfort simple souls. An example: 'Prosperity is just around the corner.' A granfalloon is a proud and meaningless association of human beings."Nanotechnology is undeniably a wampeter. I never run into people I see at nanotech meetings anywhere else. Much of the hype surrounding nanotech qualifies as foma – such promises as free, perfectly clean energy or elimination of all disease. Finally, nanotechnology has given rise to a granfalloon, in the sense that its range is so broad that attempting to capture its breadth under one canopy is ultimately meaningless.

Why this rant? Because I feel it's important to dispel the notion that there is some intrinsic value to talking about all the disparate activities of nanotechnology together; my hope is that once that is realized, we can focus on endeavors that have real value. Nanotechnology is NOT an industry. (While this assertion receives universal agreement in hallway conversations at those meetings, I inevitably hear speakers at the same meetings referring to the nanotech "industry.")

I have never heard any "definition" for nanotechnology that sounds cogent and useful, although it seems that every PowerPoint presentation is obliged to have a slide offering a definition. The other day, I even read an epistle from a nanotech high-flyer talking about the nanotech value chain! There simply is, nor can there possibly be, any such thing.

There are, however, materials, which is a large part of what people really mean when they use nanospeak. We are living in an age of materials. Our control over materials and their properties is not a sudden development, but it is one that's accelerating. The Iron and Bronze Ages were thousands of years apart, but a huge menagerie of polymers, for example, were developed in just the past 50 years! We are in the process of gaining increasing control and finesse over the structure of matter at the smallest scale (the nanoscale) where material properties emerge. This is where authentic focus of discourse and activity is, and ought to be.

Peter Grubstein and Tony Cheetham recognized this when they founded NGEN Partners in 2001. Years of incubation in university, government, and less frequently, corporate labs were beginning to hatch a number of private enterprises based on materials science advances. Yet, venture funding was scarce relative to other technology sectors such as information technology, optoelectronics and biotech. And, for good historical reasons: Materials companies have traditionally been low margin, quick to commoditize and generally lacking pizzazz. These are not favored characteristics of venture-financed companies.

But change was under way, precipitated by roughly two or three decades of federally funded university research in materials science, which had incubated nanoscale technology to the point where its leading edge seemed ripe for venture investing. Fullerenes, clays, nanocomposites, nanowires, nanotubes, dendrimers and other novel materials began populating the landscape.

Materials were being characterized in the university, as scientists will do, but in most cases, just what the materials might be useful for remained a mystery. Fullerenes provide a powerful and revealing example. As my former collaborator, Rick Smalley, has said, "Bucky still doesn't have a job." In buckyballs, we have a remarkable new chemical and material entity, with undeniably interesting properties, yet we haven't figured out what to do with it. This is generally the rule in the materials world, rather than the exception.

Much more work is required beyond discovery and characterization to bring a new material to commercial success. Even when some useful application can be found, scaling production at economic cost is far from trivial in most cases. In fact, words that strike terror in the heart of venture capitalists working the materials sector are: "It's only engineering from here on out." There is now, however, a strong pipeline flow of commercial enterprises enabled by new materials, or where old materials are applied in new ways. The venture challenge, of course, is sorting out the likely winners from the losers.

One way to minimize risk of this challenge is to obtain more and better information. This is where NGEN's model becomes valuable, and how it differentiates itself from other venture firms in the materials space: Our venture partners can dive deeply into the technical risks, and our strategic limited partners provide assistance in technical and market due diligence. Although many technology venture firms hire highly trained scientists, few firms (or none?) include a chief technology officer, which is my position with NGEN. The mix of broad technical and marketing resources lets us, as value investors, make decisions based on sound information.

Nanotechnology is not perfectly congruent with materials, but the overlap is large. New buzzwords and hype may be useful in generating excitement and funding, but likely do more harm than good if in advance of commercialization. At least that's the opinion of this reformed member of the nanotechnology granfalloon.

(SOURCE: http://www.smalltimes.com/document_display.cfm?document_id=8874)

Friday, February 04, 2005

Tuesday, February 01, 2005

A few snaps from Yosemite

Tuesday, January 04, 2005

What Social Security 'Crisis'?

What Social Security 'Crisis'?Debating ways to fix the system is wrong. Here's why. By Robert Kuttner Bush's entire plan for Social Security privatization rests on the premise that the system is in severe crisis. But a careful look at the numbers suggests that the financial crisis is largely a myth. For years, the Social Security trustees have used very conservative assumptions about future rates of economic growth, productivity growth, and growth of the labor force. These assumptions, in turn, affect the projected payroll tax collections that will fund Social Security payouts. Five years ago, in the late 1990s, they estimated the long-term economic growth rate at just 1.7 percent. The reality has been well over 3 percent. Most economists now believe the economy can do a lot better than 1.7 percent annual growth. In its 1997 report, the Trustees projected that the system would no longer be able to meet all its obligations by 2029. Just six years later in 2003, based on their acknowledgement of stronger economic growth, the Trustees moved the crisis date back to 2042. So if the system can gain thirteen years of life in six years, there's not much of a crisis. But that's just the beginning. In June, the bipartisan Congressional Budget office used more realistic assumptions about economic growth. CBO puts the first shortfall year at 2052, not 2042, and it projects Social Security's 75-year shortfall at only about four-tenths of one percent of Gross Domestic Product. Currently, that's just over $40 billion a year, or one-fifth of the revenues that the Bush administration gave up in tax cuts for the wealthy. Simply restoring pre-Bush tax rates on the richest one percent of Americans could bring the Social Security system into balance indefinitely, without reducing promised payouts by one penny. The Administration uses far rosier assumptions than the Social Security Trustees in claiming high returns for its proposed private accounts. The Administration assumes that individual portfolios will appreciate at six or seven percent a year. But if the economy is only growing at 1.7 percent a year, there is no way the stock market will achieve those results. Conversely, it we apply the Bush Administration's rosy assumptions to the present Social Security system, there is no crisis at all. The Administration has also been throwing around a particularly hysterical statistic-that Social Security faces ten to eleven trillion dollars in "unfunded liabilities." That figure is nothing but the total long-term payout that the government expects to pay retirees. But we don't calculate the rest of the budget that way. The Pentagon, for instance, spends about $400 billion a year. The Pentagon's 75-year "unfunded liability," at that rate, is $30 trillion dollars. The reason that we don't calculate budget that way, of course, is that we know government will keep collecting tax revenues, and use them to pay its obligations. Why haven't you read more about this? First, the Bush administration casts the Social Security shortfall in the most dire terms possible, to build support for its privatization scheme. In reality, that scheme will make the modest shortfall far worse, by requiring the government to go another two trillion dollars into debt. But whether to privatize, and how to make up a small shortfall, are two entirely distinct questions. Second, some Wall Street leaders and academic economists, who share a dislike of social insurance, also paint a bleak picture of the system bankrupting itself and the country. All this feeds into media assumptions. Indeed, the typical media account of the privatization debate and simply takes the premise of a system in deep crisis as if it were fact. Finally, many well-meaning Democrats who the defend the Social Security system want to be absolutely certain that its funding is rock solid. So Democrats, as well as Republicans, talk of its shortfall and offer different ways to make up the gap. Unfortunately, that tends to play into Republican hands. Republicans are counting on younger voters to support privatization. Polls show that the young have been so swayed by the talk of endless crisis that many young workers doubt whether they'll ever get anything back from the current system. To them, getting some money in the form of private accounts is at least half a loaf. In the coming debate, defenders of Social Security need to educate the public on just how solid the existing system is, and just how exaggerated is its supposed crisis. If they fail to do that, and get bogged down in a debate about how to "fix" a system that isn't really broken, the privatizers will win, and Social Security will be needlessly pillaged. Robert Kuttner is co-editor of The American Prospect. This column originally appeared in The Boston Globe. SOURCE : American Prospect Online - ViewWeb